For the People Owning the Too-Big-To-Fail Corporations

By Charles Brown

It is important to point out that the Too-big-to-fail banks and corporations

did in fact fail back in 2008; even though they were bailed out. The demand

the Wall Street rulers made to Washington for a bailout was a confession that

the whole financial system was insolvent. The USA's, We the People's, bailout brought

the finance system back from the dead. Capitalism does not add up.

After 500 years, it ends up that capitalism is bankrupt and insolvent

by its own generally accepted accounting principles.

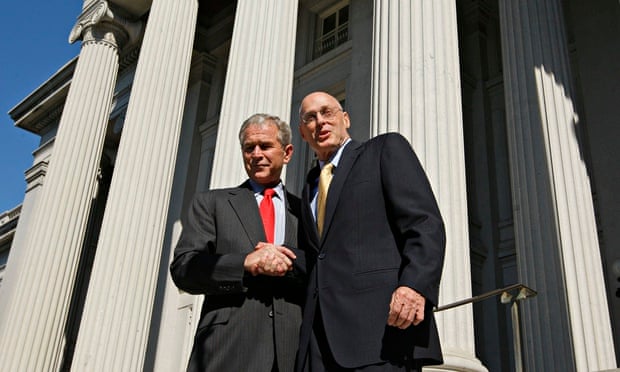

The shadowy finance ministers who ordered President Bush to bailout Wall Street,

said that certain financial institutions are "too big to fail". If they fail they will destroy the

financial system, and so the federal government must save them in order to

avoid total economic disaster for America and the world.

So, they were given trillions of dollars of what amounted to semi-gifts

( sort of "pay it back if you can at your own pace"; would that we could get

such terms in loans from these same banks)

, and the concept of "too-big-to-fail corporations"

gained wide public awareness.

Although, there was not total collapse , the bank failures that did

occur triggered the so-called Great Recession.

We, the 99%, suffered and suffer still enormously from that

recession as it resulted in all around economic distress for

tens of millions of Americans over the last six years.

These failures of the leading private institutions of

our Economy, led to an excruciating economic Depression for the Many.

Large swathes of the middle

and "lower" classes suffer poverty, foreclosure, unemployment, and the

many ways of misery, premature deaths, disease, divorce, crime, etc,

that are generated by economic downturn , especially in a jobless

recovery only for corporate profits and exploitation by the 1%

It is objectively true that this would have been worse for the 99% if

the Too-big-to-fails had not been bailed out. So, it is not the case that

these corporations should not have been bailed out, but that their Creditor,

The People, should get more for their bailout money than they did:

ownership of the big debtors.

To reiterate,_circa_ 2008, with the insolvency of financial institutions designated

Too-big-to-fails by our nation's highest financial ministers ( in other

words straight from the horse's mouth), We, the People, learned of or

were reminded of a category of economic life that had not been so

explicit in the national discourse. These Big Banks were bailed out

and avoided bankruptcy with guarantees or assurances of

anywhere from $16 to 29 trillion by the

United States of America, because the national unelected , financial ministers

declared that their failure would bring down the entire financial

industry of the US and perhaps "the West". In other words, the

insolvency of the Too-Big-To-Fail corporations was in fact the

insolvency of the whole financial system. It was a confession that

capitalism doesn't add up; it fundamentally cannot meet its own

standard of moral hazard. Wall Street's debts exceeded its assets by a

dozen or two trillion dollars, at that historic moment.

Any debtor of Wall Street creditors who reaches such a moment , must

not be bailed out because of the danger of moral hazard. If we apply

Wall Street's own standard to itself, the 2008 bailout represents the

biggest moral hazard in history, pretty much. So, the principle of

moral hazard is dead.

General Motors and Chrysler, two of our largest corporations, though

evidently an order of magnitude smaller than the Wall Street

Too-big-to-fails, were also bailed because they arer too

big to fail without devastating economic impact.

. The bailed out Too-big-to-fails, owned and controlled and

expropriated by the 1%, continue to live in fabulous luxury greater

than any ruling class in history,

There is a long history of government bailout of corporations (

(History of U.S. Gov't Bailouts

http://www.propublica.org/special/government-bailouts

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Too_big_to_fail)

The Great Recession caused many states ,including, California and Illinois, actual insolvency ,

though it was not declared; and they were bailed out of deficits by

the Obama Stimulus plan.

What is to be done now so many years from The Financial Big Bang ?

Well, like the Big Bang, it is still affecting us.

We, the People, who bailed out the Economy, must have ownership and

control of all Too-big-to-fail corporations. Private owners , who put

private interests above public interests always, cannot be trusted

with control and distribution of the products of the Economy's

Too-big-to-fail Economic Units, because their failure does not impact

the incomes of the 1% current owners, but only the lives of the masses

of people. The failure of Too-big-to-fails is dumped on the 99%, and

avoided by the 1% who own them now. The 99% must own them, therefore.

We must reverse the current circumstance in which , essentially, the

Too-big-to-fails own The People, as demonstrated by their ordering the

Presidents and Congress to give them dozens of Trillions of dollars

without their giving up ownership of themselves in exchange as would

occur in any such transaction in the "free" market. The

Too-big-to-fails still owe the People for the

Bailout. We, The Creditors, are coming to Collect.

Enact a .law :requiring the Federal Reserve to report and list quarterly on

all too-big-to-fail corporations, and initiate proceedings to take them

over. Use the same criterion as was used in the bailouts.

Enact a Law: One of the rationales for exploiting interests from debtors,

recipients of loans, is that the creditor puts its money at risk.

Since, the Too-Big-to-Fails will be bailed by the government if too

many of their loans fail, their interest rates should be abated or

negated, because they are not taking the risk they claim.

Reassert federal ownership of General Motors and Chrysler. Chrysler has been bailed out twice by the federal government.

Take Federal ownership of JP Morgan, Citibank, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, AIG and

all Wall Street, Too-big-to-fails. before they fail again.

Bailouts, bail-ins and the banks: why we can’t afford another financial crisis

http://www.theguardian.com/business/economics-blog/2014/nov/23/new-financial-crisis-bailouts-banks?CMP=fb_gu

Governments are not flush enough to contemplate a second wave of

bailouts, which leaves the problem of too ‘big to fail’ unsolved, writes

Larry Elliott

A look into the future: David Cameron’s nightmare has come true; the

slowdown in the global economy has turned into a second major recession

within a decade.

In those circumstances, there would be two massive policy challenges. The first would be how to prevent the recession turning into a global slump. The second would be how to prevent the financial system from imploding.

These are the same challenges as in 2008, but this time they would be magnified. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing have already been used extensively to support activity, which would leave policymakers with a dilemma. Should they double down on QE or come up with more radical proposals – drops of helicopter money or using QE for specified purposes, such as investment in green energy?

For now, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England prefer not to contemplate this dire possibility. They will deal with it if it happens, but are assuming it won’t.

More explicit plans have been drawn up for the big banks. The concern here is obvious. The bailouts last time played havoc with the public finances and the still incomplete repair job has required unpopular austerity. Governments are not flush enough to contemplate a second wave of bailouts. Even if they had the money, they know just how voters would react if there was talk of bailing out the bankers a second time.

As a result, there has been an attempt to ensure the globally systemically important banks (GSIBs) are better prepared to ride out a storm than they were last time. In 2008, Alistair Darling felt he had no alternative but to pump taxpayers money into RBS and Lloyds banking group because they were simply too big to fail.

Reforms pieced together by the global Financial Stability Board under the chairmanship of Mark Carney envisage solving the too big to fail problem by requiring banks to hold a lot more capital against potential losses. Instead of a bailout there would be a “bail in” – investors in the big banks would take the first hit if things went sour. The idea is not just to provide the GSIBs with larger capital buffers; it is also to remove the moral hazard – the sense that there is an implicit public subsidy that can be relied on, come what may. It is thought the guarantee of taxpayer support, even after the sort of crazy lending practices that were all too prevalent in the run-up to the crisis of 2008, was an incentive for banks to behave rashly.

Speaking

in Singapore, Carney said: “We recognise that our success can never be

absolute. Specifically, we can’t expect to insulate fully all

institutions from all external shocks, however large. But we can change

the system so that systemically important institutions, their

shareholders and their creditors bear the cost of their own actions and

the risks they take.”

This might be the case in the event that a single big institution goes pear-shaped. In the mid-1990s, for example, Barings came to grief as the result of the activities of one rogue trader, Nick Leeson. It was clearly a one-off, with no systemic implications. In those circumstances, a bail-in would work. There would be no need for the taxpayer to be involved.

But it would be a different story if it were 2008 all over again. In those circumstances, it would not just be one bank in trouble, it would be all of them. Finance ministers have to confront the same decision as the US Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, faced in September 2008 when he held the fate of Lehman Brothers in his hands: do we rescue this bank or not? No matter how big the capital buffers, no government would be prepared to take the risk.

Here’s why. The assumption is that the requirement to hold more capital will make banks more risk averse. The idea is that they will be more cautious if they have more skin in the game. This could well be true today, when memories of the last crisis are still relatively fresh, but as the late Hyman Minsky explained, stability breeds the next crisis. Investors start off being risk averse but become more and more emboldened over time. They take more risks as prices rise. They believe the only way for markets is up. They start to utter the fatal words: it’s different this time. In those circumstances, it is irrelevant whether a bank’s capital buffer is 2% or 20% of its risk-weighted assets. It won’t be enough when the crisis comes.

A second assumption is that the financial sector will accept the new arrangements in perpetuity. History suggests otherwise. Attempts will be made to water down capital requirements, and the banks will become more willing to flex their muscles as memories of the past crisis fade. Controls will be weakened just at the moment they are needed most.

The financial expert, Avinash Persaud, has identified another serious weakness in the new plans. This has to do with the way in which banks will raise the extra capital. The traditional way for a bank to hold capital is through retained earnings or financial holdings that they can turn into cash quickly. But banks have come up with a way of boosting their capital ratios without the need to hold large amounts of cash or equity. They are issuing bail-in securities, known as cocos (contingent, convertible, capital instruments) that convert into equity once a bank’s capital falls below a certain level. Cocos act like an insurance policy that can be cashed in at the appropriate moment.

The hope was that pension funds, which tend to have a long term outlook, would be the main buyers of the bail-in bonds. But so far, they have been snapped up by hedge funds, private banks and retail investors – who tend to be short-termist in their outlook and especially prone to herd-like behaviour. More and more of them are being issued to meet the demand.

You’re probably thinking what I’m thinking. Investors will pile into bail-in bonds in the way they piled in to US subprime mortgages. The bubble will eventually burst leading to a rush for the exit.

As Persaud notes in an article for the Petersen Institute for International Economics: “On such occasions these securities, which may also have encouraged excessive lending, either will inappropriately shift the burden of bank resolution on to ordinary pensioners or, if held by others, will bring forward and spread a crisis. Either way they will probably end up costing taxpayers no less and maybe more. In this regard, fool’s gold is an apt description.”

Carney believes the recent G20 summit in Brisbane marked “a watershed in ending too big to fail”. But that’s not the same as solving the problem. Before Brisbane, policy makers knew they hadn’t cracked too big to fail. After Brisbane, they mistakenly think they have.

In those circumstances, there would be two massive policy challenges. The first would be how to prevent the recession turning into a global slump. The second would be how to prevent the financial system from imploding.

These are the same challenges as in 2008, but this time they would be magnified. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing have already been used extensively to support activity, which would leave policymakers with a dilemma. Should they double down on QE or come up with more radical proposals – drops of helicopter money or using QE for specified purposes, such as investment in green energy?

For now, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England prefer not to contemplate this dire possibility. They will deal with it if it happens, but are assuming it won’t.

More explicit plans have been drawn up for the big banks. The concern here is obvious. The bailouts last time played havoc with the public finances and the still incomplete repair job has required unpopular austerity. Governments are not flush enough to contemplate a second wave of bailouts. Even if they had the money, they know just how voters would react if there was talk of bailing out the bankers a second time.

As a result, there has been an attempt to ensure the globally systemically important banks (GSIBs) are better prepared to ride out a storm than they were last time. In 2008, Alistair Darling felt he had no alternative but to pump taxpayers money into RBS and Lloyds banking group because they were simply too big to fail.

Reforms pieced together by the global Financial Stability Board under the chairmanship of Mark Carney envisage solving the too big to fail problem by requiring banks to hold a lot more capital against potential losses. Instead of a bailout there would be a “bail in” – investors in the big banks would take the first hit if things went sour. The idea is not just to provide the GSIBs with larger capital buffers; it is also to remove the moral hazard – the sense that there is an implicit public subsidy that can be relied on, come what may. It is thought the guarantee of taxpayer support, even after the sort of crazy lending practices that were all too prevalent in the run-up to the crisis of 2008, was an incentive for banks to behave rashly.

Advertisement

This might be the case in the event that a single big institution goes pear-shaped. In the mid-1990s, for example, Barings came to grief as the result of the activities of one rogue trader, Nick Leeson. It was clearly a one-off, with no systemic implications. In those circumstances, a bail-in would work. There would be no need for the taxpayer to be involved.

But it would be a different story if it were 2008 all over again. In those circumstances, it would not just be one bank in trouble, it would be all of them. Finance ministers have to confront the same decision as the US Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, faced in September 2008 when he held the fate of Lehman Brothers in his hands: do we rescue this bank or not? No matter how big the capital buffers, no government would be prepared to take the risk.

Here’s why. The assumption is that the requirement to hold more capital will make banks more risk averse. The idea is that they will be more cautious if they have more skin in the game. This could well be true today, when memories of the last crisis are still relatively fresh, but as the late Hyman Minsky explained, stability breeds the next crisis. Investors start off being risk averse but become more and more emboldened over time. They take more risks as prices rise. They believe the only way for markets is up. They start to utter the fatal words: it’s different this time. In those circumstances, it is irrelevant whether a bank’s capital buffer is 2% or 20% of its risk-weighted assets. It won’t be enough when the crisis comes.

A second assumption is that the financial sector will accept the new arrangements in perpetuity. History suggests otherwise. Attempts will be made to water down capital requirements, and the banks will become more willing to flex their muscles as memories of the past crisis fade. Controls will be weakened just at the moment they are needed most.

The financial expert, Avinash Persaud, has identified another serious weakness in the new plans. This has to do with the way in which banks will raise the extra capital. The traditional way for a bank to hold capital is through retained earnings or financial holdings that they can turn into cash quickly. But banks have come up with a way of boosting their capital ratios without the need to hold large amounts of cash or equity. They are issuing bail-in securities, known as cocos (contingent, convertible, capital instruments) that convert into equity once a bank’s capital falls below a certain level. Cocos act like an insurance policy that can be cashed in at the appropriate moment.

The hope was that pension funds, which tend to have a long term outlook, would be the main buyers of the bail-in bonds. But so far, they have been snapped up by hedge funds, private banks and retail investors – who tend to be short-termist in their outlook and especially prone to herd-like behaviour. More and more of them are being issued to meet the demand.

You’re probably thinking what I’m thinking. Investors will pile into bail-in bonds in the way they piled in to US subprime mortgages. The bubble will eventually burst leading to a rush for the exit.

As Persaud notes in an article for the Petersen Institute for International Economics: “On such occasions these securities, which may also have encouraged excessive lending, either will inappropriately shift the burden of bank resolution on to ordinary pensioners or, if held by others, will bring forward and spread a crisis. Either way they will probably end up costing taxpayers no less and maybe more. In this regard, fool’s gold is an apt description.”

Carney believes the recent G20 summit in Brisbane marked “a watershed in ending too big to fail”. But that’s not the same as solving the problem. Before Brisbane, policy makers knew they hadn’t cracked too big to fail. After Brisbane, they mistakenly think they have.

Subject: Wall Street Meltdown Primer

Bello is mostly on here, though his accounting of the 1997 Asian

financial crisis may need some revision, i.e. There is substantial

evidence that the 'crisis' was a purely US state-manufactured one: The

Clinton Administration was demanding that Thailand and Indonesia fully

open their financial markets to US finance and capital sectors. When

they objected, Clinton's Commerce Secretary, Robert Rubin, instructed

America's giant hedge funds to launch a speculative attack on the Thai

baht. The devastation then spread to Indonesia and then South Korea.

Lesson learned.

Tony

Published on Friday, September 26, 2008 by Foreign Policy in Focus

Wall Street Meltdown Primer

by Walden Bello

Many on Wall Street and the rest of us are still digesting the

momentous events of the last 10 days. Between one and three trillion

dollars worth of financial assets have evaporated. Wall Street has

been effectively nationalized. The Federal Reserve and the Treasury

Department are making all the major strategic decisions in the

financial sector and, with the rescue of the American International

Group (AIG), the U.S. government now runs the world's biggest

insurance company. At $700 billion, the biggest bailout since the

Great Depression is being desperately cobbled together to save the

global financial system.

The usual explanations no longer suffice. Extraordinary events demand

extraordinary

explanations. But first...

Is the worst over?

No. If anything is clear from the contradictory moves of the last week

- allowing Lehman Brothers to collapse while taking over AIG, and

engineering Bank of America's takeover of Merrill Lynch - there's no

strategy to deal with the crisis, just tactical responses. It's like

the fire department's response to a conflagration.

The $700 billion buyout of banks' bad mortgaged-backed securities is

mainly a desperate effort to shore up confidence in the system,

preventing the erosion of trust in the banks and other financial

institutions and avoiding a massive bank run such as the one that

triggered the Great Depression of 1929.

Did greed cause the collapse of global capitalism's nerve center?

Good old-fashioned greed certainly played a part. This is what Klaus

Schwab, the organizer of the World Economic Forum, the yearly global

elite jamboree in the Swiss Alps, meant when he said in an interview

earlier this year: "We have to pay for the sins of the past."

Was this a case of Wall Street outsmarting itself?

Definitely. Financial speculators outsmarted themselves by creating

more and more complex financial contracts like derivatives that would

securitize and make money from all forms of risk - including such

exotic futures instruments as "credit default swaps" that enable

investors to bet on the odds that the banks' own corporate borrowers

would not be able to pay their debts! This is the unregulated

multi-trillion dollar trade that brought down AIG.

On December 17, 2005, when International Financing Review (IFR)

announced its 2005 Annual Awards - one of the securities industry's

most prestigious awards programs - it had this to say: "[Lehman

Brothers] not only maintained its overall market presence, but also

led the charge into the preferred space by...developing new products

and tailoring transactions to fit borrowers' needs...Lehman Brothers

is the most innovative in the preferred space, just doing things you

won't see elsewhere."

No comment.

Was it lack of regulation?

Yes. Everyone acknowledges by now that Wall Street's capacity to

innovate and turn out more and more sophisticated financial

instruments had run far ahead of government's regulatory capability.

This wasn't because the government was incapable of regulating but

because the dominant neoliberal, laissez-faire attitude prevented

government from devising effective regulatory mechanisms.

But isn't there something more that is happening?

We're seeing the intensification of one of the central crises or

contradictions of global capitalism: the crisis of overproduction,

also known as overaccumulation or overcapacity.

In other words, capitalism has a tendency to build up tremendous

productive capacity that outruns the population's capacity to consume

owing to social inequalities that limit popular purchasing power, thus

eroding profitability.

But what does the crisis of overproduction have to do with recent events?

Plenty. But to understand the connections, we must go back in time to

the so-called Golden Age of Contemporary Capitalism, the period from

1945 to 1975.

This was a time of rapid growth both in the center economies and in

the underdeveloped economies - one that was partly triggered by the

massive reconstruction of Europe and East Asia after the devastation

of World War II, and partly by the new socio-economic arrangements

institutionalized under the new Keynesian state. Key among the latter

were strong state controls over market activity, aggressive use of

fiscal and monetary policy to minimize inflation and recession, and a

regime of relatively high wages to stimulate and maintain demand.

So what went wrong?

This period of high growth came to an end in the mid-1970s, when the

center economies were seized by stagflation, meaning the coexistence

of low growth with high inflation, which wasn't supposed to happen

under neoclassical economics.

Stagflation, however, was but a symptom of a deeper cause: the

reconstruction of Germany and Japan and the rapid growth of

industrializing economies like Brazil, Taiwan, and South Korea added

tremendous new productive capacity and increased global competition.

Meanwhile social inequality within countries and between countries

globally limited the growth of purchasing power and demand, thus

eroding profitability. The massive increase in the price of oil

aggravated this trend in the 1970s.

How did capitalism try to solve the crisis of overproduction?

Capital tried three escape routes from the conundrum of

overproduction: neoliberal restructuring, globalization, and

financialization.

What was neoliberal restructuring all about?

Neoliberal restructuring took the form of Reaganism and Thatcherism in

the North and structural adjustment in the South. The aim was to

invigorate capital accumulation, and this was to be done by 1)

removing state constraints on the growth, use, and flow of capital and

wealth; and 2) redistributing income from the poor and middle classes

to the rich on the theory that the rich would then be motivated to

invest and reignite economic growth.

This formula redistributed income to the rich and gutted the incomes

of the poor and middle classes. It thus restricted demand while not

necessarily inducing the rich to invest more in production.

In fact, neoliberal restructuring, which was generalized in the North

and South during the 1980s and 1990s, had a poor record in terms of

growth: global growth averaged 1.1% in the 1990s and 1.4% in the

1980s, whereas it averaged 3.5% in the 1960s and 2.4% in the 1970s,

when state interventionist policies were dominant. Neoliberal

restructuring couldn't shake off stagnation.

How was globalization a response to the crisis?

The second escape route global capital took to counter stagnation was

"extensive accumulation" or globalization. This was the rapid

integration of semi-capitalist, non-capitalist, or precapitalist areas

into the global market economy. Rosa Luxemburg, the famous German

revolutionary economist, saw this long ago as necessary to shore up

the rate of profit in the metropolitan economies: by gaining access to

cheap labor, by gaining new, albeit limited, markets, by gaining new

sources of cheap agricultural and raw material products, and by

bringing into being new areas for investment in infrastructure.

Integration is accomplished via trade liberalization, removing

barriers to the mobility of global capital and abolishing barriers to

foreign investment.

China is, of course, the most prominent case of a non-capitalist area

that was integrated into the global capitalist economy over the last

25 years.

To counter their declining profits, many Fortune 500 corporations have

moved a significant part of their operations to China to take

advantage of the so-called "China Price" - the cost advantage of

China's seemingly inexhaustible cheap labor. By the middle of the

first decade of the 21st century, roughly 40-50% of the profits of

U.S. corporations were derived from their operations and sales abroad,

especially China.

Why didn't globalization surmount the crisis?

This escape route from stagnation has exacerbated the problem of

overproduction because it adds to productive capacity. A tremendous

amount of manufacturing capacity has been added in China over the last

25 years, and this has had a depressing effect on prices and profits.

Not surprisingly, by around 1997, the profits of U.S. corporations

stopped growing. According to one index, the profit rate of the

Fortune 500 went from 7.15% in 1960-69 to 5.3% in 1980-90 to 2.29% in

1990-99 to 1.32% in 2000-2002.

What about financialization?

Given the limited gains in countering the depressive impact of

overproduction via neoliberal restructuring and globalization, the

third escape route became very critical for maintaining and raising

profitability: financialization.

In the ideal world of neoclassical economics, the financial system is

the mechanism by which the savers or those with surplus funds are

joined with the entrepreneurs who have need of their funds to invest

in production. In the real world of late capitalism, with investment

in industry and agriculture yielding low profits owing to

overcapacity, large amounts of surplus funds are circulating and being

invested and reinvested in the financial sector. The financial sector

has thus turned on itself.

The result is an increased bifurcation between a hyperactive financial

economy and a stagnant real economy. As one financial executive notes,

"there has been an increasing disconnect between the real and

financial economies in the last few years. The real economy has

grown...but nothing like that of the financial economy - until it

imploded."

What this observer doesn't tell us is that the disconnect between the

real and the financial economy isn't accidental. The financial economy

has exploded precisely to make up for the stagnation owing to

overproduction of the real economy.

What were the problems with financialization as an escape route?

The problem with investing in financial sector operations is that it

is tantamount to squeezing value out of already created value. It may

create profit, yes, but it doesn't create new value. Only industry,

agricultural, trade, and services create new value. Because profit is

not based on value that is created, investment operations become very

volatile and the prices of stocks, bonds, and other forms of

investment can depart very radically from their real value. For

instance, in the 1990s, prices of stock in Internet startups

skyrocketed, driven mainly by upwardly spiraling financial valuations

rooted in theoretical expectations of future profitability. Share

prices crashed in 2000 and 2001 when this strategy got completely out

of hand. Profits then depend on taking advantage of upward price

departures from the value of commodities, then selling before reality

enforces a "correction." Corrections are really a return to more

realistic values. The radical rise of asset prices far beyond any

credible value is what what fosters financial bubbles.

Why is financialization so volatile?

With profitability depending on speculative coups, it's not surprising

that the finance sector lurches from one bubble to another, or from

one speculative mania to another.

And because it's driven by speculative mania, finance-driven

capitalism has experienced scores of financial crises since capital

markets were deregulated and liberalized in the 1980s.

Prior to the current Wall Street meltdown, the most explosive of these

were the string of emerging markets crises and the U.S.tech stock

bubble's implosion in 2000 and 2001. The emerging markets crises

primarily included the Mexican financial crisis of 1994-95, the Asian

financial crisis of 1997-1998, the Russian financial crisis in 1998,

and the Argentine financial collapse that occurred in 2001 and 2002,

but they also rocked other countries including Brazil and Turkey.

One of President Bill Clinton's Treasury Secretaries, Wall Streeter

Robert Rubin, predicted five years ago that "future financial crises

are almost surely inevitable and could be even more severe."

How do bubbles form, grow, and burst?

Let's first use the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, as an example.

First, capital account and financial liberalization took place

Thailand and other countries at the urging of the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) and the U.S. Treasury Department. Then came the

entry of foreign funds seeking quick and high returns, meaning they

went to real estate and the stock market. This overinvestment made

stock and real estate prices fall, leading to the panicked withdrawal

of funds. In 1997, $100 billion fled the East Asian economies over the

course of just a few weeks.

That capital flight led to an IMF bailout of foreign speculators. The

resulting collapse of the real economy produced a recession throughout

East Asia in 1998. Despite massive destabilization, international

financial institutions opposed efforts to impose both national and

global regulation of financial system on ideological grounds.

What about the current bubble? How did it form?

The current Wall Street collapse has its roots in the technology-stock

bubble of the late 1990s, when the price of the stocks of Internet

startups skyrocketed, then collapsed in 2000 and 2001, resulting in

the loss of $7 trillion worth of assets and the recession of

2001-2002.

The Fed's loose money policies under Alan Greenspan encouraged the

technology bubble. When it collapsed into a recession, Greenspan, to

try to counter a long recession, cut the prime rate to a 45-year low

of one percent in June 2003 and kept it there for over a year. This

had the effect of encouraging another bubble - in real estate.

As early as 2002, progressive economists such as Dean Baker of the

Center for Economic Policy Research were warning about the real estate

bubble and the predictable severity of its impending collapse.

However, as late as 2005, then-Council of Economic Adviser Chairman

and now Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke attributed the

rise in U.S. housing prices to "strong economic fundamentals" instead

of speculative activity. Is it any wonder that he was caught

completely off guard when the subprime mortgage crisis broke in the

summer of 2007?

And how did it grow?

According to investor and philanthropist George Soros: "Mortgage

institutions encouraged mortgage holders to refinance their mortgages

and withdraw their excess equity. They lowered their lending standards

and introduced new products, such as adjustable mortgages (ARMs),

'interest-only' mortgages, and promotional teaser rates." All this

encouraged speculation in residential housing units. House prices

started to rise in double-digit rates. This served to reinforce

speculation, and the rise in house prices made the owners feel rich;

the result was a consumption boom that has sustained the economy in

recent years."

The subprime mortgage crisis wasn't a case of supply outrunning real

demand. The "demand" was largely fabricated by speculative mania on

the part of developers and financiers that wanted to make great

profits from their access to foreign money that has flooded the United

States in the last decade. Big-ticket mortgages were aggressively sold

to millions who could not normally afford them by offering low

"teaser" interest rates that would later be readjusted to jack up

payments from the new homeowners.

But how could subprime mortgages going sour turn into such a big problem?

Because these assets were then "securitized" with other assets into

complex derivative products called "collateralized debt obligations"

(CDOs). The mortgage originators worked with different layers of

middlemen who understated risk so as to offload them as quickly as

possible to other banks and institutional investors. These

institutions in turn offloaded these securities onto other banks and

foreign financial institutions.

When the interest rates were raised on the subprime loans, adjustable

mortgage, and other housing loans, the game was up. There are about

six million subprime mortgages outstanding, 40% of which will likely

go into default in the next two years, Soros estimates.

And five million more defaults from adjustable rate mortgages and

other "flexible loans" will occur over the next several years. These

securities, the value of which run into the trillions of dollars, have

already been injected, like virus, into the global financial system.

But how could Wall Street titans collapse like a house of cards?

For Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Bear

Stearns, the losses represented by these toxic securities simply

overwhelmed their reserves and brought them down. And more are likely

to fall once their books - since lots of these holdings are recorded

"off the balance sheet" - are corrected to reflect their actual

holdings.

And many others will join them as other speculative operations such as

credit cards and different varieties of risk insurance seize up. The

American International Group (AIG) was felled by its massive exposure

in the unregulated area of credit default swaps, derivatives that make

it possible for investors to bet on the possibility that companies

will default on repaying loans. According to Soros, such bets on

credit defaults now make up a $45 trillion market that is entirely

unregulated. It amounts to more than five times the total of the U.S.

government bond market. The huge size of the assets that could go bad

if AIG collapsed made Washington change its mind and intervene after

it let Lehman Brothers collapse.

What's going to happen now?

There will be more bankruptcies and government takeovers. Wall

Street's collapse will deepen and prolong the U.S. recession. This

recession will translate into an Asian recession. After all, China's

main foreign market is the United States, and China in turn imports

raw materials and intermediate goods that it uses for its U.S. exports

from Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia. Globalization has made

"decoupling" impossible. The United States, China, and East Asia in

general are like three prisoners bound together in a chain-gang.

In a nutshell...?

The Wall Street meltdown is not only due to greed and to the lack of

government regulation of a hyperactive sector. This collapse stems

ultimately from the crisis of overproduction that has plagued global

capitalism since the mid-1970s.

The financialization of investment activity has been one of the escape

routes from stagnation, the other two being neoliberal restructuring

and globalization. With neoliberal restructuring and globalization

providing limited relief, financialization became attractive as a

mechanism to shore up profitability. But financialization has proven

to be a dangerous road. It has led to speculative bubbles that produce

temporary prosperity for a few but ultimately end up in corporate

collapse and in recession in the real economy.

The key questions now are: How deep and long will this recession be?

Does the U.S. economy need another speculative bubble to drag itself

out of this recession? And if it does, where will the next bubble

form? Some people say the military-industrial complex or the "disaster

capitalism complex" that Naomi Klein writes about will be the next

bubble. But that's another story.

Copyright © 2008, Institute for Policy Studies

Too big to fail

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a theory in economics. For the 2009 Andrew Ross Sorkin book, see Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System—and Themselves. For the film based on the book, see Too Big to Fail (film).

The "too big to fail" theory asserts that certain financial

institutions are so large and so interconnected that their failure would

be disastrous to the economy, and they therefore must be supported by

government when they face difficulty. The colloquial term "too big to

fail" was popularized by U.S. Congressman Stewart McKinney in a 1984 Congressional hearing, discussing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's intervention with Continental Illinois.[1] The term had previously been used occasionally in the press.[2]Proponents of this theory believe that some institutions are so important that they should become recipients of beneficial financial and economic policies from governments or central banks.[3] Some economists such as Paul Krugman hold that economies of scale in banks and in other businesses are worth preserving, so long as they are well regulated in proportion to their economic clout, and therefore that "too big to fail" status can be acceptable. The global economic system must also deal with sovereign states being too big to fail.[4][5][6][7]

Opponents believe that one of the problems that arises is moral hazard whereby a company that benefits from these protective policies will seek to profit by it, deliberately taking positions (see Asset allocation) that are high-risk high-return, as they are able to leverage these risks based on the policy preference they receive.[8] The term has emerged as prominent in public discourse since the 2007–2010 global financial crisis.[9] Critics see the policy as counterproductive and that large banks or other institutions should be left to fail if their risk management is not effective.[10][11] Some critics, such as Alan Greenspan, believe that such large organisations should be deliberately broken up: “If they’re too big to fail, they’re too big”.[12] More than fifty prominent economists, financial experts, bankers, finance industry groups, and banks themselves have called for breaking up large banks into smaller institutions.[13]

In 2014, the International Monetary Fund and others said the problem still had not been dealt with.[14][15] While the individual components of the new regulation for systemically important banks (additional capital requirements, enhanced supervision and resolution regimes) likely reduced the prevalence of TBTF, the fact that there is a definite List of systemically important banks considered TBTF has a partly offsetting impact.[16]

Definition

Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke also defined the term in 2010: "A too-big-to-fail firm is one whose size, complexity, interconnectedness, and critical functions are such that, should the firm go unexpectedly into liquidation, the rest of the financial system and the economy would face severe adverse consequences." He continued that: "Governments provide support to too-big-to-fail firms in a crisis not out of favoritism or particular concern for the management, owners, or creditors of the firm, but because they recognize that the consequences for the broader economy of allowing a disorderly failure greatly outweigh the costs of avoiding the failure in some way. Common means of avoiding failure include facilitating a merger, providing credit, or injecting government capital, all of which protect at least some creditors who otherwise would have suffered losses...If the crisis has a single lesson, it is that the too-big-to-fail problem must be solved."[17]Bernanke cited several risks with too-big-to-fail institutions:[17]

- These firms generate severe moral hazard: "If creditors believe that an institution will not be allowed to fail, they will not demand as much compensation for risks as they otherwise would, thus weakening market discipline; nor will they invest as many resources in monitoring the firm's risk-taking. As a result, too-big-to-fail firms will tend to take more risk than desirable, in the expectation that they will receive assistance if their bets go bad."

- It creates an uneven playing field between big and small firms. "This unfair competition, together with the incentive to grow that too-big-to-fail provides, increases risk and artificially raises the market share of too-big-to-fail firms, to the detriment of economic efficiency as well as financial stability."

- The firms themselves become major risks to overall financial stability, particularly in the absence of adequate resolution tools. Bernanke wrote: "The failure of Lehman Brothers and the near-failure of several other large, complex firms significantly worsened the crisis and the recession by disrupting financial markets, impeding credit flows, inducing sharp declines in asset prices, and hurting confidence. The failures of smaller, less interconnected firms, though certainly of significant concern, have not had substantial effects on the stability of the financial system as a whole."[17]

- http://billmoyers.com/episode/full-show-too-big-to-fail-and-getting-bigger/

http://network.nationalpost.

Bailout marks Karl Marx's comeback

Posted: September 29, 2008, 8:03 PM by Jeff White

Martin Masse, mortgage crisis

Marx’s Proposal Number Five seems to be the leading motivation for

those backing the Wall Street bailout

By Martin Masse

In his Communist Manifesto, published in 1848, Karl Marx proposed 10

measures to be implemented after the proletariat takes power, with the

aim of centralizing all instruments of production in the hands of the

state. Proposal Number Five was to bring about the “centralization of

credit in the banks of the state, by means of a national bank with

state capital and an exclusive monopoly.”

If he were to rise from the dead today, Marx might be delighted to

discover that most economists and financial commentators, including

many who claim to favour the free market, agree with him.

Indeed, analysts at the Heritage and Cato Institute, and commentators

in The Wall Street Journal and on this very blog, have made

declarations in favour of the massive “injection of liquidities”

engineered by central banks in recent months, the government takeover

of giant financial institutions, as well as the still stalled

US$700-billion bailout package. (Editor's Note: Scholars at the Cato

Institute have not supported Washington’s $700-billion financial

bailout plan. The National Post apologizes for the error.) Some of the

same voices were calling for similar interventions following the burst

of the dot-com bubble in 2001.

“Whatever happened to the modern followers of my free-market

opponents?” Marx would likely wonder.

At first glance, anyone who understands economics can see that there

is something wrong with this picture. The taxes that will need to be

levied to finance this package may keep some firms alive, but they

will siphon off capital, kill jobs and make businesses less productive

elsewhere. Increasing the money supply is no different. It is an

invisible tax that redistributes resources to debtors and those who

made unwise investments.

So why throw this sound free-market analysis overboard as soon as

there is some downturn in the markets?

The rationale for intervening always seems to centre on the fear of

reliving the Great Depression. If we let too many institutions fail

because of insolvency, we are being told, there is a risk of a general

collapse of financial markets, with the subsequent drying up of credit

and the catastrophic effects this would have on all sectors of

production. This opinion, shared by Ben Bernanke, Henry Paulson and

most of the right-wing political and financial establishments, is

based on Milton Friedman’s thesis that the Fed aggravated the

Depression by not pumping enough money into the financial system

following the market crash of 1929.

It sounds libertarian enough. The misguided policies of the Fed, a

government creature, and bad government regulation are held

responsible for the crisis. The need to respond to this emergency and

keep markets running overrides concerns about taxing and inflating the

money supply. This is supposed to contrast with the left-wing

Keynesian approach, whose solutions are strangely very similar despite

a different view of the causes.

But there is another approach that doesn’t compromise with

free-market principles and coherently explains why we constantly get

into these bubble situations followed by a crash. It is centered on

Marx’s Proposal Number Five: government control of capital.

For decades, Austrian School economists have warned against the dire

consequences of having a central banking system based on fiat money,

money that is not grounded on any commodity like gold and can easily

be manipulated. In addition to its obvious disadvantages (price

inflation, debasement of the currency, etc.), easy credit and

artificially low interest rates send wrong signals to investors and

exacerbate business cycles.

Not only is the central bank constantly creating money out of thin

air, but the fractional reserve system allows financial institutions

to increase credit many times over. When money creation is sustained,

a financial bubble begins to feed on itself, higher prices allowing

the owners of inflated titles to spend and borrow more, leading to

more credit creation and to even higher prices.

As prices get distorted, malinvestments, or investments that should

not have been made under normal market conditions, accumulate. Despite

this, financial institutions have an incentive to join this frenzy of

irresponsible lending, or else they will lose market shares to

competitors. With “liquidities” in overabundance, more and more risky

decisions are made to increase yields and leveraging reaches dangerous

levels.

During that manic phase, everybody seems to believe that the boom will

go on. Only the Austrians warn that it cannot last forever, as

Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises did before the 1929 crash, and as

their followers have done for the past several years.

Now, what should be done when that pyramidal scheme starts crashing to

the floor, because of a series of cascading failures or concern from

the central bank that inflation is getting out of control? It’s

obvious that credit will shrink, because everyone will want to get out

of risky businesses, to call back loans and to put their money in safe

places. Malinvestments have to be liquidated; prices have to come down

to realistic levels; and resources stuck in unproductive uses have to

be freed and moved to sectors that have real demand. Only then will

capital again become available for productive investments.

Friedmanites, who have no conception of malinvestments and never raise

any issue with the boom, also cannot understand why it inevitably

leads to a crash.

They only see the drying up of credit and blame the Fed for not

injecting massive enough amounts of liquidities to prevent it.

But central banks and governments cannot transform unprofitable

investments into profitable ones. They cannot force institutions to

increase lending when they are so exposed. This is why calls for

throwing more money at the problem are so totally misguided.

Injections of liquidities started more than a year ago and have had no

effect in preventing the situation from getting worse. Such measures

can only delay the market correction and turn what should be a quick

recession into a prolonged one.

Friedman — who, contrary to popular perception, was not a foe of

monetary inflation, but simply wanted to keep it under better control

in normal circumstances — was wrong about the Fed not intervening

during the Depression. It tried repeatedly to inflate but credit still

went down for various reasons. This is a key difference in

interpretation between the Austrian and Chicago schools.

As Friedrich Hayek wrote in 1932, “Instead of furthering the

inevitable liquidation of the maladjustments brought about by the boom

during the last three years, all conceivable means have been used to

prevent that readjustment from taking place; and one of these means,

which has been repeatedly tried though without success, from the

earliest to the most recent stages of depression, has been this

deliberate policy of credit expansion. ... To combat the depression by

a forced credit expansion is to attempt to cure the evil by the very

means which brought it about ...”

The confusion of Chicago school economics on monetary issues is so

profound as to lead its adherents today to support the largest

government grab of private capital in world history. By adding their

voices to those on the left, these confused free-marketeers are not

helping to “save capitalism”, but contributing to its destruction.

Financial Post

Martin Masse is publisher of the libertarian webzine Le Québécois

Libre and a former advisor to Industry minister Maxime Bernier.

Photo: Karl Marx

Editor's Note: Scholars at the Cato Institute have not supported

Washington’s $700-billion financial bailout plan. The wording of a

sentence in Martin Masse’s

September 30 commentary, “Karl’s Comeback,” mistakenly implied

otherwise. The National Post apologizes for the error.

Read more: http://network.nationalpost.

Hello dear blog admin.

ReplyDeleteHave a nice day. Thanks for your awesome blog post. I am appreciate to read your blog.

Attention please-

Many employees are exposed to the hazards of industrial diseases because of their occupations. People who suffer from vibrating finger are liable to be compensated by their employers. The civil legal advisors assist people in getting their due claims.

Regards

Angelina Jukic

Look about: civil Legal Service